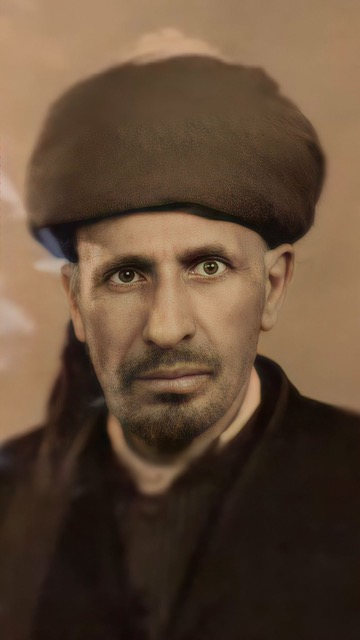

Sheikh Mahmoud (courtesy of Nizar Khatib)

The Stone House, June 7, 1967.

Blessedly the war was short. I was a newlywed. Nineteen years old. An American Jew from NYC who married into a Palestinian family from East Jerusalem, Jordan after a very brief courtship— an unlikely occurrence. Faisal and I were busy planning our honeymoon to Petra. Attention to warnings of imminent war were ignored by our joy. But when the sound of explosions came from the direction of Jerusalem and the night sky lit with flares, we could no longer ignore the obvious. War had broken out. Keeping a promise to Faisal’s Khelty Hind, we walked about 6 kilometers from Qalandia to her apartment in Ramallah. Khelty lived alone. And she was scared. But by the time we arrived, her ground floor apartment was filled with families from the upper stories. Faisal and I were welcomed as newlyweds and offered the only bedroom. Mattresses were strewn all over the floor in the rest of the apartment. Woman were busy turning flour into bread while there still was electricity. Candles and matches were gathered as precious items. We had no idea how long we’d be hold up in Khelty Hind’s apartment.

Blessedly the war was short, only six days according to history books. But when the Egyptian Air Force, exposed on the tarmac was destroyed in a matter of hours, the war was effectively over. We had survived. Immediately after the war, the border between East Jerusalem, Jordan and West Jerusalem, Israel, known as No Man’s Land, was fluid.

The Jaffa Gate, on the edge of this internationally recognized border, had been closed for eighteen years. Faisal, and I were among the first people to walk through. Built in 1538 by Suleiman the Magnificent, the Jaffa Gate was the beginning or the end of the road that led to Hebron and the ancient port city of Jaffa. In Arabic it is called Bab al-Khalil, meaning the Gate of the friend, a reference to Ibrahim/Abraham entombed in Hebron. Under Ottoman rule this was the main egress between the Old City and the newer environs of west Jerusalem. In 1948, when the Jews were unable to conquer the Old City, the Israeli commander, Moshe Dayan, and his Jordanian counterpart, Abdullah a-Tal, sat in a deserted house near the Mandelbaum Gate in Jerusalem and hastily drew drew a two-mile cease fire line with a green marker which became known as the Green Line.

Faisal was five years old the last time he walked through the Jaffa Gate into this area called “No Man’s Land” because it was known to have been littered with land mines, but we felt no sense of danger. Israeli soldiers had swept the area. Without the intrusion of people or traffic for almost two decades, vegetation rioted between barbed wire, rocky hillsides, refuse, and abandoned homes. Oleander bushes with little need for water proliferated alongside white jasmine and thistles. Untended for so long, olive, fig, and almond trees matured into exotic shapes. Faisal was searching for his grandfather’s house in a village once known as Al-Baqaa.

Sheikh Mahmoud, scribe, mystic, scholar, and personal astrologer to Abdul Hamid, the last Ottoman Sultan to hold power, had not been forgotten. Faisal’s mother once told this story: “Your grandfather. Sheikh Mahmoud was born around 1872 in a tiny village called az-Zahiriyeh, about twenty-two kilometers southwest of Hebron. When the Sheikh was nine, a mysterious stranger from India showed up in the village guest house run by his father. In those days, a guest had the right to three days of free lodging and food. But on the fourth day, it was ok to ask for money.”

Mahmoud asked the guest, “Why did you come here?”

“I have come here for you.” replied the guest. Mahmoud disappeared with the stranger and returned 13 years later carrying strange books, and a purse with different currencies. He also returned with strange powers. Faisal’s mother believed her son had inherited many of his grandfather’s gifts.

Other people wandered through this landscape. Enterprising Palestinian farmers had already set up makeshift stands where they sold fresh watermelon. Decades of solitude for No Man’s Land was over. I was not convinced that Faisal’s childhood memories would lead him to a lost past, but he recognized the house immediately.

The flat-roofed building stood intact under the canopy of a leafy fig tree. Broken and missing windowpanes testified to the house’s vacancy. Overgrown vines blanketed stone walls. Wild irises and hollyhocks sprouted randomly near stone steps leading to a door that proved to be unlocked. The desert sun burned hot outside, but inside the house was cool. Faisal reached for a handful of figs. Tasting the fruit seemed to evoke childhood memories.

“I loved visiting Sidi here. One day my grandfather gave my older sister a bag of candy, and me half a British pound. I got so jealous. My clever sister said, ‘I’ll give you my bag of candy if you give me the piece of paper Sidi gave you.” Faisal laughed. “She cheated me.” Later that afternoon guns started shooting. We ran up the steps and lay down on the floor in Khalti Asma’s room. She was my mother’s half-sister who died of cancer at a young age. Bullets flew over our heads. They left deep holes in the stone walls.” Faisal had no idea how long the attack lasted, but the terror from that day left an indelible imprint on a young boy growing up in British Mandate Palestine.

Faint flecks of violet and gold paint remained on the inside wall of the room that once belonged to Khalti Asma. Strewn all over the floor in the otherwise empty rooms were papers and notebooks, yellowed from time and streaked with animal excrement. We wiped filth off the pages as if handling the Rosetta stone. Under a pile of debris in the corner of the room lay a faded cloth sack tied with silk thread. Inside was a handwritten Quran.

“This book is over one hundred years old,” Faisal said, tracing his fingers around the intricate design on the inside cover. The brittle pages threatened to become dust under his touch. He slipped the Quran back into the sack and continued to examine the musty papers while I went to sit in the shade of the fig tree, dreaming of what it might be like to live here.

“Ahlan wa sahlan,” I imagined saying to guests leaning against soft pillows scattered around the room. “Be welcomed in our home. Our home is your home.” We would serve sweet mint tea with baklava while telling the story of how we found Sheikh Mahmoud’s house in No Man’s Land.

Faisal’s voice broke my reverie. “Erees,” he said excitedly, “there are handwritten letters from King Farouk of Egypt thanking my grandfather for his dream interpretations. (Footnote: Farouk I ruled Egypt from 1936 until overthrown in a coup d’etat in 1952 led by Colonel Gamel Abdel Nasser whose influence reduced Arab reliance on Western powers and increased Arab connection with the Soviet Union.)

Faisal found letters from Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Born in Karachi, British controlled India, Ali Jinnah became a lawyer who voiced the notion of a secular democratic Muslim state carved out of British-ruled India, similar to partitioning a Jewish state in British Mandate Palestine. Ali Jinnah advocated for Hindu-Muslim unity, but later came to believe Muslims needed a state of their own. Pakistan was created after widespread violence and the death of hundreds of thousands of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs. What advice did Sheikh Mahmoud offer to Ali Jinnah, the father of modern Pakistan. And what advice would he offer now?

Believing he would return within weeks, Faisal’s grandfather unwittingly abandoned his home. He was not alone. In April of 1948, the village of Deir Yassin was attacked by two Jewish militias, the Stern Gang and the Irgun.The villagers believed they were safe from militias because Deir Yassin was eighteen miles outside the boundaries of the Jewish state, as delineated by the UN partition plan. The massacre of 254 people, including women and children, led to widespread panic across Palestine. During the course of the war, over 700,000 Palestinian-Arabs were expelled from their homes, more than 500 villages were destroyed, and over 4 million acres of land were confiscated. Weeks and months of people waiting to return home, became generations of people living in refugee camps scattered across the Middle East. The Sheikh remained in exile in Egypt until he walked to Ramallah, Jordan where he was eventually buried. This moment in Palestinian history is called Al-Nakba— The Catastrophe.But in my family, the UN proclamation officially establishing the independent Jewish State of Israel on May 14, 1948, was cause for celebration.

The afternoon passed quickly. We were bursting to tell Faisal’s family about Sheikh Mahmoud’s stone house. Gathering the correspondence, unfinished manuscripts, and handwritten Quran, we carried our miraculous harvest back through No Man’s Land. We entered the Old City through the Jaffa Gate feeling as triumphant as Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1898, when thousands lined the streets to welcome the visiting German monarch and his wife, Augusta Viktoria. We walked through the Jaffa Gate like General Allenby did in 1917, when he led British soldiers into Jerusalem, signifying the end of four hundred years of Ottoman rule. General Allenby immediately proclaimed the Holy City to be under martial law but assured people that “every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected, and every person was free to pursue his lawful business without interruption.” In 1967, a similar declaration from the Israelis would have been very welcomed.

But Faisal and I were not visiting or triumphal dignitaries. The next day, accompanied by Amty, Ibrahim, Samira, and Marwan, we returned to the stone house ready to picnic in the shade of the fig tree. But we were too late! The house was gone without a trace! So was the leafy fruit-filled tree! Concrete and stone mixed with mangled uprooted trees, shrubs, and garbage. We walked in circles, not believing the devastation. An army of bulldozers had leveled the area—for a park, we were told. Instead of the anticipated figs, we ate dust mixed with tears that formed rivulets of grief running down our cheeks. No trace of the neighborhood remained except in the hearts of those who would never forget.

Shocked by the loss, our procession walked slowly back through No Man’s Land, through the Jaffa Gate, returning to a home that no longer felt like a sanctuary. Hope, a rare commodity in this part of the world, had been crushed along with the stone house —and the fruiting fig tree.

Leave a comment